News

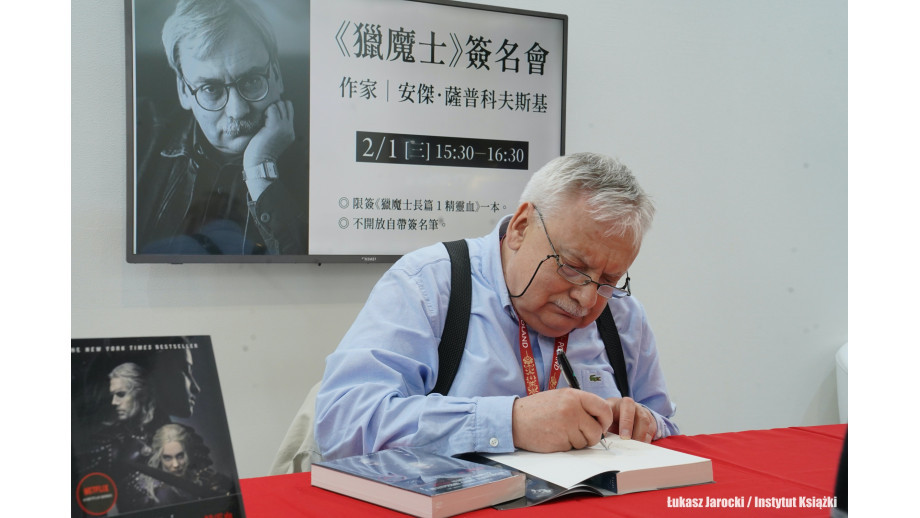

Bedside table #90. Andrzej Sapkowski: books shaped me and got me into writing

Andrzej Sapkowski talks about the books that have impressed him lately, how he came to be a writer, about the rehabilitation of speculative fiction, as well as explains why the fantasy genre has been assigned "the derogatory label of escapism"

Marlon James wrote of Neil Gaiman: "Like Borges, he writes about things as if they have already happened, describes worlds as if we are already living in them, and shares stories as if they are solid truths that he’s just passing along.” To me, that's what escapism is - reading your books and stories makes me feel like I'm living in your world. What is escapism for you?

I understand that we are talking about literature, not psychiatry. And in literature, it's short: escapism is an escape into the world of literary fiction, full stop. The most common, though, is for the word 'escape' to be understood as something shameful and contemptible - like a cowardly escape from the battlefield, an escape from one’s duties, or ultimately, an escape from normal life.

Meanwhile, the Latin etymology of ‘excappare’ literally means to take off one's cloak, while figuratively it means to free, to liberate from something that hinders and weighs one down. The Polish language also knows another escape - the 'escape of sinners' from the Loreto prayer, understood as a rescue, an asylum. A bit better, isn't it?

Without exception, every fictional reading is an escape into fiction. The book creates its own fictional reality, it doesn't matter if it is that of Bilbo Baggins, Mr Wokulski, or the Count of Monte Christo. And if a reader plunges into it, it is not desertion or escape from life, but this very ‘excappare’ - the removal of the cloak, the shell that is the lack of imagination. Loreto asylum. As Tolkien put it: if the world of fiction is an escape, it is by no means in the sense of a cowardly desertion from reality, but an escape from the dark dungeon in which our lack of imagination imprisons us.

In an interview, you said that the fantasy genre has been assigned the 'derogatory label of escapism'. What do you think is the reason for this?

The label was of course given by those who despised the genre. They attempted to argue that the fantasy reader sacredly believes in what they read about, i.e. elves, dragons and witchcraft, that they have a pentagram and black wax candles on the floor at home, and that they go to fantasy conventions dressed as Gandalf. Or that the fantasy reader is an eternal boy, inept in life, and a loner fearful of the opposite sex, a freak in general. The reality is frightening for such an individual, so they must seek escape in fantasy books, role-playing games, and Japanese animations. Escape, a cowardly desertion from everything - in other words, escapism in its purest form, understood in the worst way.

What's more, reading fantasy doesn't just attract freaks and misfits - it creates them. Influenced by a fixation on fantasy, the most mentally and physically healthy individual will beyond any doubt lose their marbles. Sooner or later, fantasy will mess with their heads, make them cut themselves off from the world, believe in the hereafter, dragons, magic and dress up as Sailor Moon.

It is quite sad that some of the authors of the above derogatory fantasy hogwash really believed it. And they do. But well, as they say: beauty is in the eye of the beholder.

It is possible that, due to the war in Ukraine and the economic crisis, quite a few people need an escape into a fantasy world, but doesn't fantasy literature sometimes bring us face to face with what we fear?

Ursula Le Guin, drawing heavily on Jung, described the fantastic archetypes in fantasy as wild and dangerous wildernesses, a journey through which can change us. Expose the fears hidden in the subconscious. I would emphasise: our fears.

Reading fantasy will not inflict fears on us, it can only reveal those that lie dormant within ourselves.

Marlon James also recalled what Toni Morrison said about Tolstoy, who 'couldn’t have had an idea that he was actually writing for a little coloured girl in Lorraine, Ohio'. Who did you write The Witcher saga for?

Someone seems to have got carried away here. Tolstoy was certainly not writing for a little coloured girl in Lorraine, Ohio. If one assumes at all that he had a certain writing target, it was more likely to be the mature ladies of St Petersburg. Instead, it can be assumed that Tolstoy never imagined that his work would reach an Ohio girl. Nor Uncle Tom's cabin. Nor the kolkhoz library in Mala Kakovka. With that, indeed, I could agree. And what about me, you ask? Well, with me it was the same as with Tolstoy.

What do you learn about your books and short stories when meeting foreign readers?

My own knowledge of my own books is neither enriched nor diminished by readers - whether domestic or foreign. At meetings with readers, on the other hand, you can learn a lot about the readers themselves. Just why would anyone need to know this? Terry Pratchett once said that only a foolish writer doesn't listen to their fans, but only a foolish writer does what they want. In my humble opinion, Pratchett was only half right.

From the books you read, which ones contributed to your desire to become a writer yourself?

There were too many for me to be able to make a list. I was an avid reader from a young age, the first books - I remember them - my father read to me when I could not yet read myself. Books have shaped me, yes, undoubtedly, and books got me into writing. But I won't be able to give you specific titles.

Vladimir Nabokov claimed that one cannot read a book, one can only reread it, and that “a good reader, a major reader, an active and creative reader is a rereader'. Should books really be reread?

There are, that's for sure, books that you return to and that you would like to return to - and that's because they are so good. There are also some that may not be as good, but carry some emotional charge, evoke nostalgia. Anyway, these are individual matters. To each his own, de gustibus, and so on. By the way, in the Nabokov statement quoted, in order to understand it properly, you have to replace 'books' with 'my books'.

What have you read recently and what are your impressions of these readings?

Maybe not so recently, and I'll just mention the ones of the many that were particularly good reads: Eoin Colfer Highfire, Suzanne Collins The Ballad Of Songbirds And Snakes, Stephen King Billy Summers, Holly Black Book of Night, Stephen King Fairy Tale, Robert Harris Act of Oblivion, R. F. Kuang Babel, Peng Shepherd The Cartographers. Impressions? They are all well written, read in one breath. And that, after all, is what it's all about, n'est-ce-pas?

Can you say of any of the books you have read in recent years that it is a masterpiece or that it has dazzled you?

Madeline Miller, Circe. V. E. Schwab, The Invisible Life of Addie LaRue. Hervé Le Tellier, L’Anomalie.

What was it about them that dazzled you?

Dazzle is a big word. Well written and that's it. And as much as that.

Michel Houellebecq wrote in an essay on Lovecraft: ”Those who love life do not read. Nor do they go to the movies, actually. No matter what might be said, access to the artistic universe is more or less entirely the preserve of those who are a little fed up with the world.” Do you share this escapist opinion of the French writer or not necessarily?

To be honest, I share few of Houellebecq's opinions. I would venture to say that - of those I know - none. With particular regard to the one quoted.

In Olga Tokarczuk's opinion, fantasy should stand up for itself and erode unjust prejudices, if only from those who regard fantasy as something made up and therefore of incomplete value. How can these prejudices be eroded, if at all possible?

Prejudices - and their higher form, the so-called 'ubzdury' (‘preju-drivel’ – translators’ note) - have it in their nature that they are impossible to fight. And there is no discussion because what happens is the phenomenon of being deaf to reasoning.

We know this for example from political life, from television. As for the fantasy, it was enough to give it time. Not so long ago, this genre was looked upon with utter contempt, and serious literary experts were not even allowed to mention it. Not so long ago, so-called critics were grumbling about the Oscars awarded to The Lord of the Rings. And for the Nike Award nomination awarded to me. Today, no one would call Ursula Le Guin, Margaret Atwood, Stephen King, or Neil Gaiman niche authors anymore, and a critic who would omit Game of Thrones from a list of all-time series would be trifled with. And Radek Rak received a Nike Award. And Tokarczuk also got the Booker and the Nobel Prize. We did not have to wait long.

To summarise, not so long ago, the response, 'I don't read fantasy' meant: "I only read serious and dignified stuff". Today it means: "I'm a dimwit".

Interviewer: Michał Hernes

Translated by Justyna Lowe