News

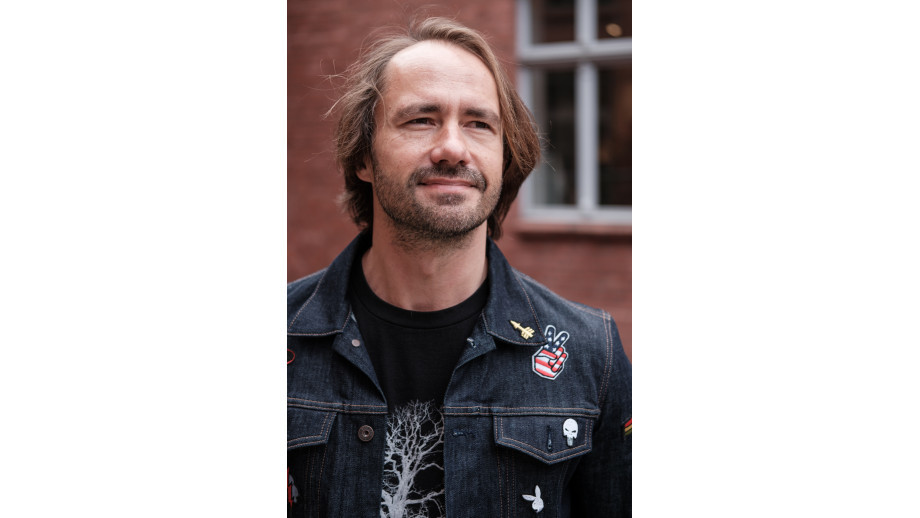

Bedside table #67. Łukasz Musiał: I do not search for recipes for a good life in literature

Łukasz Musiał, a literary scholar, essayist, and translator, talks about, among other things, an offensive of ideologicality and the misconstrued conception of moralising in the reflection on literature, the political character and autonomy of literature, the insatiability of life that leads to reading, his experience of translating Kafka and Walser, as well as the Great PWN Encyclopaedia, which shaped his way of looking at the world.

"To read like one has read so far? Is this still possible, is this allowed, is this the right thing to do?," you ask in the introduction to your essay collection Zaufanie i utopia (“Trust and Utopia”), published in 2019, immediately adding that you don't know the answer to this question. Has the last year, the year of the pandemic, of the global crisis (socio-economic, but probably also - partly because of the way information circulated at the time – cognitive crisis), somehow updated your view on this issue? In other words: how to read when the world is in flames?

I think the world is still a long way from being said to be all in flames. Each generation tends to regard its experiences as unique and exceptionally difficult. Which is not to say that there is no validity whatsoever in your statement. Indeed, I sometimes feel a great dissonance between what is going on around me, in the world, and what is going on inside me. Between the sort of thrust of reality (I am thinking, for example, of the effects of the world pandemic) and the way my life is, including my professional life, which has stabilised a great deal over the last few months. Just like with many people in my 'industry', the pandemic has given me a comfort in my work previously unknown to me to this extent: I have even more time to read books and write about them. To carry out my reading and writing plans in peace. To, so to speak, re-evaluate values. I see what is happening thanks to the media coverage, of course. Not only thanks to them, because in my immediate environment, there are also cases of people who have been badly affected by fate and illness. I personally was very lucky; I survived this period without any major health upheaval. It may sound selfish, but never mind: I have really taken a liking to my current life. I came to like this unique opportunity to unhurriedly shape my intellectual journey. There have been very many books I have read over the past year, from a wide variety of fields. I am an eclectic reader by nature, the pandemic period has only reinforced this inclination. Perhaps it was also due to this thrust of reality that we are talking about? It certainly provokes me to reflect time and again.

I am a Germanist by education, and I have always been very interested in German-language literature of the first decades of the twentieth century, and it is not difficult to find parallels there with our present day. Almost exactly one hundred years ago, one of the most terrible wars in history ended. Although we haven’t experienced such a war, we are shaken by powerful crises: economic, migration, environmental, and any other. A century or so ago, a pandemic was also raging around the world, the so-called 'Spanish flu'. In addition, the economic crisis gradually deepened, especially in Germany, where inflation was rampant at the turn of the second and third decades of the 20th century, and people were very uncertain about the future. On top of this, traditional social structures, state forms, and old political arrangements were disintegrating. When it comes to Germany back then, almost everything was changing, and in an extremely short period of time. As was the case then, a natural reaction to the rapid changes taking place is an ideologisation of attitudes and a general oversensitivity that makes it very difficult to assess the situation sensibly. There is a clear tendency to stand on the barricades, to take sides, to dramatically highlight the differences that divide us. Also, the tendency to dogmatism, to obstinacy, to the pompous solemnity with which one declares one's own position. Consequently, many participants in these disputes show an inability to relax, even for a moment. This also applies to literature - writers, critics, researchers. I am observing – this trend may have already emerged before, but the socio-political unrest of recent years and then the pandemic have certainly reinforced it - an offensive of ideologicality and misconstrued conception of moralising in reflections on literature and the humanities in general. Much more often than in the past, I come across representatives of the literary or academic community who are convinced that literature should strongly take sides in political and social conflicts, expressing its stance on, for example, ethical, ecological, and economic issues. I think that some currents of ecocriticism or Olga Tokarczuk's concept of the "tender narrator", a notion that has made a huge career in our country, are very good examples of this attitude. It is based on the conviction that the narrator, i.e. the one who speaks to us, as it were, from "the inside of" literature, should look at the world with particular care, sensitivity, or tenderness indeed, and then tell us about it in such a way that we, the readers, change it for the better. I do understand the noble intentions behind the concept, it's just that I myself am certainly not looking for recipes for a good life and a good world in literature. And I am not always looking for tenderness either. On the contrary, I think a healthy dose of ruthlessness or hooliganism does writers good. For in literature, I look for images of the complexity of life and the complexity of the world. I find such images very much absent in contemporary literature, especially in Polish literature. At least in adult literature, because children's and young people's literature does much better in this respect. Contrary to what one might assume, it is much less didactic, but much more unruly, unpredictable. Much more "flexible" when it comes to the worlds, value systems, and perspectives presented in it. And thus, much more interesting. The same applies to comics, and in particular to so-called graphic novels. Meanwhile, among the creators of 'adult' literature, as well as among critics and researchers, the habit of unnecessary moralising is spreading. It is as if they all insist that they are now going raise us, which is simply a form of acting from a position of power. Left-wing or right-wing, it makes no difference. Those who want to distance themselves from this risk being considered "indifferent", socially useless, sometimes even amoral.

More and more often, I come across a kind of misconstrued mentoring, a superior tone, a constant preoccupation, a kind of sanctimoniousness, stemming perhaps from the conviction that one knows better than others how to run our world. That is why, by the way, so-called socially engaged literature, which is not only supposed to describe the world but also, as I heard recently, to want good things for it, is being rewarded more and more often these days. Intellectuals, on the other hand, are sometimes called - I actually read something like this a few weeks ago - a 'public good', which should be available to citizens who want to understand more about reality. Forgive the sarcasm, but in cases like this I get the impression that someone here is practising 'command-and-control' humanism or working towards their future beatification. Such a superior attitude is completely alien to me. Besides, I am sure of one thing: good literature and good science are not made with good intentions, no matter what those intentions are. And most importantly: literature and science are not created with the intention of raising anyone. That is a blind alley.

And how do you understand the politicalness of literature? Couldn't the very form of literature, or the place from which the author speaks to us, be evidence of the political nature of literature?

I understand the intentions behind the conviction of the politicalness of all literature, but I don't sympathise with them either. I have long been an advocate of the views of Hannah Arendt, who believed that each of us citizens, that is, members of a particular social community, state, or whatever, should have a particular private space to which no unauthorised person has easy access; which no one will impulsively disturb with their views, judgments, or opinions. They will not tread on it with their boots, even if their intentions are the most noble. Talks are important, discussions are important, disagreements are important. Exchanges of views are, of course, also important. These are truisms. But it is also important to respect others' right to their own views, judgements, and opinions. Another person’s right to be wrong. And to privacy. We all have a huge problem with this, especially in Poland, which is divided into so many tribes that are hostile to one another. And each of these tribes is brandishing great slogans. It wants to judge and control the 'others'. Instead of sometimes just trusting. In short, I would like to see less politics and more privacy, also in literature and in literary research and criticism. We should not abuse the concept of politicalness and look for it in our every gesture, word, view, or attitude. To say that everything is political is a sign of bad taste and a gross oversimplification.

Do you therefore believe in the possibility of autonomy for highly artistic literature, for example in relation to the commodity market?

Literature ceased to be autonomous at the latest in the eighteenth century, when the publishing market and all the institutions associated with it developed rapidly. It was then that literature became consistently subject to the law of massification and commodification, the law of supply and demand. This trend intensified in the following century, when significant technical progress was made in the production and distribution of books, for example, much more efficient printing presses were constructed. For people professionally involved in the publishing market, reading meant more and more: to check a literary text for its market value. Will it be suitable for publication or not? Will I make or lose money on it? It was then that literature, this "high" literature too, became part of the global capitalist market, for better or for worse. For better, because in many ways it was able to grow faster and more vigorously and, most importantly, to gain many new readers. For worse, because it has just become a commodity for sale, the same as shoes, ham, a decorative necklace, a hammer, a cow. Let us dream for a moment: wouldn't it be beautiful if the only law of art was the law of supply? Of course, within the literary field, we are not - we, the people who live from literature - always and absolutely a commodity. As authors, we can sometimes preserve a space of freedom and liberty, and even sometimes consciously expand it. I am just not convinced that this freedom and liberty is really as great as we, clerks, often think. I myself, for example, as one of the actors in the academic or publishing world, am strongly entangled in various dependencies, including personal ones, which at times serve my work and sometimes pose a serious obstacle to it. Oh well, these are the rules of the game. Either we accept them, or we remain on the fringes of the academic, publishing, or literary field. In the worst-case scenario, we are excluded from these fields altogether. This also happens, for various reasons. This issue was brilliantly analysed in relation to academic circles a long time ago by Pierre Bourdieu in his book Homo academicus, which unfortunately has not been translated into Polish and is almost unknown here. It is a pity. We, Polish literary scholars and critics could learn a lot from it. Writers too, after all, they are part of this gigantic system of formal and informal relationships. A good example is the institution of the literary award, which in a frightening number of cases is turning into an unhealthy patron-client relationship. But this is a topic for a separate discussion.

Indeed, you are both an academic and an essayist. To what extent can this uninhibited essay form fit into the parameterised academic world?

In my academic, essayistic, and critical work I have never - fortunately or not - been concerned about such issues. And I still don't really care about them, even though not caring about them is getting harder every year. In Poland in particular, one can see a progressive obsession with parameterisation. I believe that, in spite of the tiredly repeated postulates of the "internationalisation of science", this obsession only proves our deep mental provincialism. I simply divide texts into good and bad, that is my only criterion. My profession gives me the great satisfaction of being able to pursue my private passions through it. Or obsessions! It's a rare privilege, and I appreciate it, although I would prefer to be paid a little bit better after all. [laughter] I can also try out different languages, different forms of communication. I care about maintaining the right balance between the perspective of a literary historian, which formally I am, and the perspective of Łukasz Musiał, who approaches the text with his life, his experiences, moods, emotions, thoughts. I think the most fun for me is trying to balance these two perspectives and find some tertium comparationis, which is usually difficult, even very difficult, at least for me. I have been working on this for about twenty years with varying degrees of luck.

In Trust and Utopia, you write, "I have always felt close to the ideal of literature as a pedagogical institution, a kind of Castalia, a republic of scholars and artists". It would therefore be about - probably important in your reflection on literature - the German ideal of Bildung, formation and education. Do you think literature truly updates, expands our knowledge of the world and life?

If we are talking here about a form of pedagogy, it is only 'soft' pedagogy, not the kind of pedagogy I criticised earlier, which was bred into cheap moralising. For I’ll repeat myself to the point of exhaustion: moralising is fundamentally alien to me. Bildung is not about making people moral, turning them into angels through books. Educating the readers, shaping them, is simply about the comprehensive development of their personality. So that they can deal effectively with the unimaginable complexity of life. The complexity of life and life experiences is a challenge for everyone, including me. I learn to know this complexity very often through literature, although of course there are other methods, other paths, no less interesting and effective.

So, you haven't become a 'better person' thanks to literature?

Certainly not. I hope I haven't become worse either! [laughter] Instead, it seems to me that thanks to literature, I simply know and feel more. Definitely more. That I have become better acquainted with the complexity of life, which I am constantly talking about here. I don't look for a commonality of experience in books, as is often nicely put, because that would mean I only want to learn about what I already know. No, what I want to tear out of books is their otherness. But incidentally, you touch on another important point: after all, one could put it all like this: If you really want to learn about the complexity of life, you should throw books into a corner and go out onto the street. Approaching people, getting to know them, travelling. In short, to live and thus accumulate experiences. Unfortunately, it is not that simple when it comes to practice.

We all live in smaller or larger social capsules, social monads, surrounded by people we know, usually like somehow, who usually share our views, have similar professions and experiences to our own. And yet, beyond these capsules, beyond these monads, there are millions of other worlds, much harder to access, or sometimes not at all. Even with the best intentions, we remain human beings who spend most of our lives within a limited circle of experience. Overall, it's quite boring and predictable. Thanks to literature - or various forms of art in general - it is sometimes possible to transcend this cursed circle. You can better understand how the world and human beings work. Yes, we are all similar to each other in some way, but we are also different in our histories, our behaviour, our views, our emotions, our traditions. I'm still hungry for other people's stories. I am hungry for experience, hungry for life. I think that is mainly the reason why I read books. And that is also why I write about them.

Continuing the Bildung theme: what were the readings that shaped you? The ones that you imbibed when you were young and which, in some significant way, have influenced how you perceive literature today.

You might be surprised, but when I think back to my first readings, I think primarily of their materiality, so to speak. So, books as objects. I grew up in a house with mainly books from the 1950s and 1960s, collected in my youth by my mother and father. I remember their smell very well, having "inhaled" it as a child in the 1980s and afterwards: that specific mixture of mould, dust, the cloths that were used to wipe them, the breaths that settled on the paper over time. The colour of these books, the colour of old pages, yellowed, with cracked, warped covers... These are all the first associations that come to my mind - not the specific titles, but the matter from which the books are woven. The sentiment for those scents, colours, and textures has remained with me to this day. To this day, I prefer, whenever possible of course, to reach for old editions of books, such as literary classics. New books are not for me. I don't like books that have just left the printing press, editorially polished, "dandified", "primped". And I absolutely hate the shiny white of young paper. Oh well, my little quirks. But your question was probably heading in a slightly different direction. So yes, I obviously remember a lot of books that have marked me in some way for the future. However, one that has regularly accompanied me for many years, from the moment I started reading until high school and even beyond, was the Great PWN Encyclopaedia from the 1960s (Great Universal Encyclopaedia PWN [State Scientific Publishers] - the largest Polish encyclopaedia ever written [until 2005] – translator’s note). First of all, it was physically attractive to me. [laughter] I really liked its classic elegance, the dark green colour of the covers, the old-fashioned smell, the paper soft yet flexible and strong. And the numerous signs of wear and tear that I naturally love: coffee stains, tea stains, food stains, scribbles, notes in the margins and the like. Secondly, I often found myself reading this encyclopaedia like a novel, i.e. entry by entry. Of course, the encyclopaedia is a novel of a very particular kind. It can be read linearly, but no coherent plot emerges from it. Nevertheless, I am convinced that it is this type of reading that has shaped my mind to a decisive degree. It has shaped the way I see the world, the way I read and write. And as I have mentioned, I read and write in a very eclectic way, reaching for very different books by very different authors from very different eras. Each of them opens the door to completely different worlds and it is exactly the same case with an encyclopaedia - each entry is a different idea, a different concept, a different event, a different character, a different fact. Each is a gateway to another world, to another reality. And to another consciousness. Together, they all form a kind of multiverse, but one whose centre cannot be determined; one that has no single root. It rather resembles a monstrous collection of rhizomes. All the same, the encyclopaedia also creates a kind of higher order, a kind of summation. A kind of Borgesian The Library of Babel, very eclectic and manifold, diverging in various directions, thematically tangled, multiplying internally by budding, proliferating.

Interesting. When I was a child, I used to pester my mother with questions about the meanings of various words. Eventually, she bought me a dictionary so that I could look them up myself. I remember reading that dictionary, also the PWN one, very similar to what you're talking about now – entry by entry, or at random. There is probably a whole category of books that accompany us constantly but that we do not at first consider formative. I believe a dictionary must be important for you as a translator, too. What is a dictionary for you, also in its broad sense - a dictionary for reading, writing, and translation?

It’s a good question, I've been thinking about this a bit recently too, while working on a book about Robert Walser. I decided to write it differently from all the previous ones. Because that is what Walser himself requires of me. Of course, with every author, and with me too, specific style traits can be delineated. I mean the style of reception, the style of thinking, the style of interpretation, but also simply the language itself. However, when I think back to the books, articles, essays, critical texts, introductions, and afterwords that I have written, which are, after all, very numerous, I do not have the impression that there is any coherent whole emerging from them - and I am very happy about that because, as I said, I am always most attracted to eclecticism. I like to think of myself as a nomad, as effectively changing my styles. Working as a translator certainly helps with that, and a lot. Naturally, I cannot completely transcend myself; I have my horizon, beyond which I probably will not go, no matter how hard I try. But the horizon has a way of always being far away, doesn't it? So, in theory, you can go on ahead indefinitely. And this hope, perhaps illusory, I hold on to.

Do your translations form a certain canon or rather a separate line? Do you choose the texts you want to translate?

I might surprise you, but I don't have the classic translator temperament, that is, it's not something I enjoy doing in life the most. I do not translate for a living, fortunately. I translate mostly what I want. Of course, this was not always the case. At the beginning - during my doctoral studies - I simply wanted to earn some extra money, so I took on a wide variety of assignments. For many years, I was mainly involved in translating scientific literature intended for the academic world. I am referring, for example, to the numerous books published in the excellent series of scholarly publications Poznańska Biblioteka Niemiecka (“Poznan German Library”), headed for many years by Professor Hubert Orlowski, my intellectual master. Or, as I sometimes like to call him, my master Yoda, after all my name is Luke. [laughter] I rarely translated fiction in those days. The first book of this kind in my translation output was Ernst Jünger's mini-novel Sturm. It is only in recent years that I have found myself translating fiction more often. I am fortunate that it is wonderful. Kafka, as I am now referring to him, is an author whom every German translator probably dreams of translating. I composed a volume entitled Prozy utajone (“Concealed Prose”) for the State Publishing Institute (PIW), which was received, I think, very well. The following book, much more extensive and much more demanding to read, will be Kafka's Diaries in my translation, which is already finished anyway. After the publication of this book, I would like to say goodbye to Kafka for a while. I feel it's time for another entry in this private "encyclopaedia" of mine, another door that will lead me to another "universe". I am thinking of the prose of Robert Walser. I am about to finish a book on his work. I also plan to translate his works.

What appeals to you about Robert Walser's work? In your texts about him, you mention the "cheeky cheerfulness" that the works of the author of The Robber emanate.

Note that it is extremely difficult to speak in the language of literature and literary research about such things as cheerfulness, joy, happiness, trust, goodness. We look for words that don't sound naïve, and we usually don't succeed very well. Since the Romantic era, we have become accustomed to the idea that outstanding literature should focus on the ‘tribulations of existence' of one kind or another. To this day, this is the dominant view both among writers of literature as well as its scholars and critics. "Happiness," Walser wrote at one point, sarcastically of course, "is not good writing material. It is content with what is. It needs no commentary. Curled up in a ball, it can sleep like a hedgehog. Suffering and tragedy, on the other hand, have an explosive power. It is only necessary to light the fuse at the right moment. Then, they take off like rockets, lighting up the whole space. If an artist wants to produce something interesting, they have to bring a demon with them". On the other hand, Maria Poprzęcka, an art historian, once wrote, with regret, that "masterpieces do not laugh". Finally, someone else stated that happy people do not create imperishable things. In recent years, I myself have spent a lot of time in the area of "dark" literature, penetrating the numerous " tribulations of existence" I’ve just mentioned. I have explored trauma, violence, the experience of death. Kafka himself provided me with a whole bunch of intriguing thoughts here, not to mention other authors. However, for some time now, I have been growing convinced that in the long run, it has something of taking the easy path about it. For if we, as writers and readers, concentrate on other people's suffering with such tenderness and respect, surely, we should concentrate on happiness with equal respect? Why ignore it? Meanwhile, for some reason, happiness, carefreeness, or cheerfulness seem intellectually 'shallow', of little use for conceptual, philosophical, or literary analysis. Imagine we were to offer students a whole-semester seminar on happiness in literature. How difficult it would be to find texts for such classes! Good texts, naturally, because poor ones abound. How difficult it would be to find an interesting language with which to talk about happiness in literature. When we have to discuss trauma, exclusion, suffering, oppression, about the extermination of European Jews in the 1930s and 1940s, then we easily find the right texts and the right language. We can spend years working on all this until retirement, developing these beautiful discourses of ours, intellectually so refined. In short, an adequate conceptuality, thanks to which we manage to tame, at least intellectually, the "tribulations of existence" is available in excess, whereas when faced with happiness, cheerfulness, and carefreeness - we are intellectually virtually defenceless. Look, we have a plethora, in Poland and throughout the world, of research centres devoted to Holocaust studies. Very well. But why don't we have research centres on Survivors? Why should Survivors stand lower than the Holocaust in this arbitrary hierarchy, as if death were more important than life and violence more important than a helping hand? I want to be correctly understood: we are all affected by the “tribulations of existence”, that is an indisputable fact. And we all try to cope with them in some way. I simply ask, why has literature taken such a one-sided liking to them? Yes, there is no shortage of books in the history of literature defending cheerfulness and simple but important human desires, but how many of them have made it to the first league of high literature? How many of these are we returning to now? Anatol France, Bohumil Hrabal, Italo Calvino - writers who at one time were popular, even very popular. Read, feted, awarded. But then the literary historians come and push their work into the background. And they run to their Strindbergs, Bernhards, Sebalds, Kafkas. Because all that matters is the damned "tribulations of existence". Who reads France today? In Zorba the Greek, a beautiful tale about the desire for life, whatever it may be, one increasingly sees only sexism, misogyny, and 'cheap' wisdom. Hrabal and Calvino have also, to put it plainly, lost out on historical-literary value, and wrongly so. I feel that in the nineteenth century, 'high' literature began to lose that certain kind of suppleness that it still displayed in the eighteenth century; that it specialised too much in 'tragic' language, and in the 20th century, this tendency only increased. And yet, every specialisation is somewhat of an easy option, because a specialist is someone who has the right tools to make their job easier. That is why we have a whole range of outstanding writers, literary scholars, and critics, specialised in the “tribulations of existence”, those who understand literature and the world through pain. And I hardly know any who "specialise" in goodness and happiness, and do so in an artistically or intellectually interesting way. Who would intelligently, that is without moralising and cheap sanctimoniousness, describe a beautiful and good world. Over the years, I have become more convinced that the image of the world that emerges from the greatest masterpieces of so-called "high" literature is very often simply a caricature of that world. It is as if it has been established that a writer's status is directly proportional to the way they perceive pain. That is why I dream of writing a book in which I take up 'joyful' writing. "Being-toward-death", as Heidegger wanted? Perhaps I lack a sense of the tragic, but I think that this 'being-toward-death' is a gross exaggeration. Nietzsche wanted 'joyful wisdom’; I call for joyful writing.

So, does looking for cheerfulness in literature attract you as a certain challenge? A difficulty?

Perhaps many years of reading Kafka have predisposed me to such an exploration. I do not want to be misunderstood: Kafka was, is, and probably will remain the great literary love of my life. However, after years of research and translation, at some point, I felt weary of this arch-rich, yet somehow one-sided vision of reality. A ''Kafkaesque'' vision, to use an appropriate term. Who knows, perhaps one only becomes an outstanding writer if one presents such an original, consistent and, to some extent, skilfully trimmed vision of the world and of man? Anyway, I felt tired. I thought Robert Walser would be a good antidote. Not only to Kafka, but also to a whole range of outstanding writers I have read in my life. For their works themselves often deepen our existential uncertainty, rather than simply describing it, as is often mistakenly believed.

In a way, reading Walser is much harder than reading Kafka. Probably because we still lack the right interpretative tools. For Kafka we have plenty of them, one can even pick through them. Meanwhile, Walser still eludes us, in that joyful, carefree way of his, in that persistent 'cheerfulness' of his, in that bizarre and consistent belief that the world is essentially good, that people are fundamentally good; that there is no need to improve anything in this world, and in people either. It is an exceptional attitude compared to other authors of modernist literature. Or even literature in general, the "high" kind, obviously. It really fascinated me. In the midst of such a dark, pessimistic era - an era of "the flowers of evil", "crime and punishment", "inferno" or other "dark towers" - someone is creating artistically remarkable literature which - to quote one of Walser's texts - "wants to press the world to its chest". This is what I find to be the greatest research difficulty. The optimism of Walser's characters is much harder to write about than the traumatic experiences of Kafka's characters. It is necessary to invent, I feel, a whole new language for this. I try to do that in my new book.

And what are you reading now besides books that interest you research-wise? What are your holiday reads?

I returned years later to Curzio Malaparte. The first time, I didn't understand him one bit. I was repelled by his ruthlessness, outraged by his cynicism, including his moral cynicism. I now perceive his prose very differently. Today, it does not outrage me but inspires me. In a situation where so many writers, scholars, and critics want to angelise me, I perversely choose authors such as de Sade, Céline, Ernst Jünger, Bukowski, Littell. Or Malaparte. This is perfectly sobering for me. Yes, I'm going to Italy soon and for this reason, among other things, I reached for The Skin and Kaputt. But I reached for these masterful novels also because I fancied a piece of ostentatiously 'insensitive' literature; a decent literary fucking monster of a book.

Interviewer: Jakub Nowacki

Translated by Justyna Lowe