News

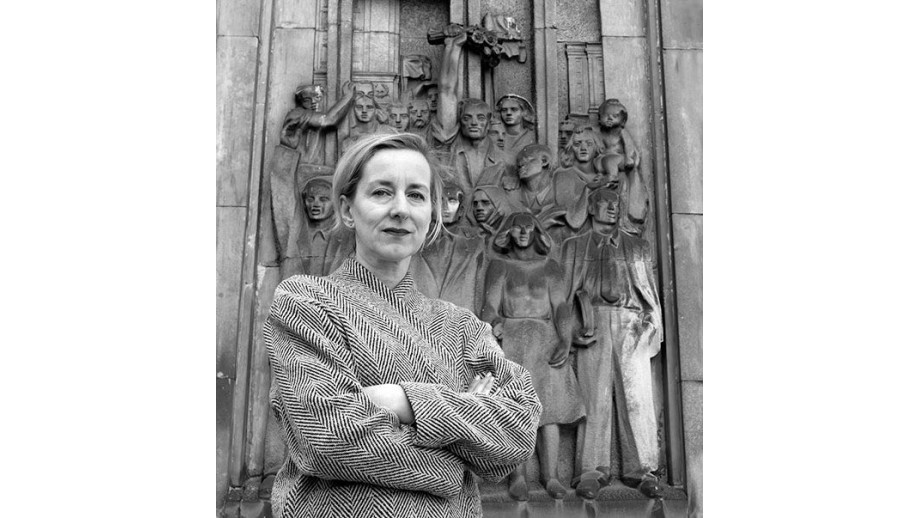

Bedside table #61. Dominika Buczak: I have always been interested in women's stories

“It seemed to me that reportage could tell the story of life to the fullest. Now, a vision of the world distilled from reality in good prose works better for me,” says journalist and prose writer Dominika Buczak.

Do you use a bedside table? And if so, what lingers on it?

Of course, I have books lingering, not just by my bed and not just on the bedside table. I read books for pleasure, for development, and for work. I have several current piles. On one of them - on the windowsill right next to my desk - lined up in a row are the books I need to create the world of my new novel. The world is completely unknown to me, so there is quite a pile growing. I have already read some of these titles, but I need to review them again - for example, Maria Janion's Kobiety i duch inności (“Women and the Spirit of Otherness”) or Svetlana Alexievich’s The Unwomanly Face of War. But there are also some that I have read for the first time, such as Wielka Trwoga (“The Great Fear”) by Marcin Zaręba, Ich matki, nasi ojcowie (“Their Mothers, Our Fathers”) by Piotr Pytlakowski, or Victims’ Revenge by Helga Hirsch. I have been getting down to read some of them for years. Now their moment has come.

There's also a lot of old stuff borrowed or bought from online second-hand bookshops – Henryk Worcell’s short stories, for example. They are all covered with coloured post-its and filled with my comments. Each page I write costs me reading several others.

And what do you read after work?

After work, I mainly read novels. When I was working intensively as a journalist, I was mostly interested in non-fiction literature. It seemed to me that reportage could tell the story of life to the fullest. Now, a vision of the world distilled from reality in good prose works better for me.

I read a lot of novels. On my Kindle - a virtual stack - I now have the book Andreowia by Beata Chomątowska. I enjoyed the book very much because it was set in the environment of Krakow journalists, which I had been getting to know from the inside for seven years. After all, the author herself used to work for a Krakow newspaper. Beata has created an apt satire on Krakow, on journalists, and on Krakow's journalists.

I am also reading Arundhati Roy's The God of Small Things and Magda Szabó's The Door in parallel. These two books are the aftermath of a list published online by Elena Ferrante (at least her publisher claims she is a mysterious writer). On the list, Ferrante lists 40 contemporary novels that she considers the most important and these are exclusively books written by women. What an invigorating prospect! I've always been interested in stories told by women, but I found I had quite a few titles to catch up with. I am reading them one after the other, and it's a real relief after the male-centric worldview that surrounds us from everywhere. It is like bathing in an equal though alternative perspective. I recommend novels written by women, and I don't mean at all that they are better. It’s the same case as with those written by men - they are various. But they often speak of the erased, the whispered, the unscripted.

It is interesting to note that Ferrante recommends books written by female authors from all over the world, from Japan to Hungary. I read those that have been translated into Polish, and others, I listen to in English. Recently, The Years by Annie Ernaux. Or rather Les Années because the author is French. And this book is very French and very unusual, a kind of collective generational memoir. It is rumoured that Ernaux's columns are soon to be published in Polish, but Les Années is unlikely to be.

Are audiobooks just another virtual pile?

Until recently, I thought I would never listen to audiobooks, but I started running and they have proved to be great companions. I listen mostly in English - I follow the Booker and Pulitzer Prizes. I have just listened to Shuggie Bain by Douglas Stuart, a New Yorker originally from Glasgow. The protagonist of this novel is a boy whose mother suffers from alcoholism and falls into increasing problems. This fantastic novel, winner of the Booker Prize, will be published in Polish in the middle of the year. And I will read it again then, because the Scottish accent (the story is set in Glasgow), especially in the dialogue parts, was very tiring. However, Betty Smith's A Tree Grows in Brooklyn, an iconic tale about the poorer part of New York, which I listened to just before Shuggie Bain, read by an actress with a fantastic Brooklyn accent – pure pleasure.

A lot of new titles are being published now, which of them can count on your interest?

I try to keep up to date with new titles, especially if they describe the world as seen from alternative perspectives: women, any minorities, non-heterosexual people, underprivileged groups. I will definitely read Robert Nowakowski's Ojczyzna jabłek (“Homeland of Apples”), I am looking forward to Bernardine Evaristo's Girl, Woman, Other and Marieke Lucas Rijneveld's The Discomfort of Evening. Novels bring me the most reading satisfaction today. And I've developed such filters that I use when choosing books that I actually rarely come across something that disappoints me.

Apart from novels, I follow closely everything that concerns women. I am very interested in intellectual analysis of the situation of women in the world and feminist thought. I have just read Kobiety w Polsce, 1945-1989. Nowoczesność – równouprawnienie – feminizm ("Women in Poland, 1945-1989. Modernity - Equality - Feminism") by Małgorzata Fidelis, Barbara Klich-Kluczewska, Piotr Perkowski, and Katarzyna Stańczak-Wiślicz. Soon, the courier will deliver Invisible Women by Caroline Perez Criado and The Double X Economy by Linda Scott. Recently, the bag of this subject matter has been untied. Finally!

What is the difference between reading for pleasure and professional reading, or does such a division not make sense?

When reading as part of documentation, my vigilance sharpens to those facts I need for writing a novel. Sometimes, one sentence from an entire book resonates so strongly that it creates a scene, or even gives direction to the whole story.

In a short article from the Życie Warszawy daily from 1952, I found a story about a student who was so devoted to social work that she neglected her studies and who was subjected to a peer tribunal conducted by the Union of Polish Youth. I introduced it to Plac Konstytucji ("Constitution Square") and a lot of what happened in the novel was due to Mania being so dedicated to building the MDM Housing Estate that she failed her finals.

On the other hand, I recently found one sentence in The Great Fear that was memorable, poignant, and it moved me. I'm going with it in the next novel. This is a great book that helped me understand the emotional climate of the post-war period, but for that one sentence alone it was worth reading.

When I read 'after hours', I am not as focused, although it is no longer an innocent reading pleasure unmarked by the shadow of analysis. In my head, I am constantly checking how the story has been told, from which side, how the protagonist has been constructed, what their relationship with the world is. The brain constantly analyses data.

However, there comes a point during the writing process when I am unable to read other authors. I become so absorbed in the story I'm creating that others distract me.

Which childhood readings have you recommended to your sons?

There have been many such books, but not all have worked. Both sons were gripped by one of the beloved books of my childhood, James and the Giant Peach by Roald Dahl. It has now been published in a new translation and under a different title, but we have a copy at home which I got from my mother with a dedication for my sixth birthday. We love it, all three of us. After James, we started reading other stuff by Dahl - Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, Fantastic Mr Fox, Matilda.

The children enjoyed the classics, The Secret Garden, Five Children and It, and the other books by Edith Nesbit, or Karolcia ('Caroline') by Maria Kruger. And, of course, Astrid, not only the funny ones but also the sadder stories. The boys love The Brothers Lionheart and Mio, my Son.

The books I read avidly when I was a teenage girl did not work very well. Neither Bahdaj nor Nienacki surprised them. Also, they don't like my once favourite Hanna Ożogowska. Then again, I was struck by some passages I didn't see as a child. Ożogowska depicts patriarchal family relations, and my children ask: why does the girl make breakfast for her father, why does she clean the house, why does her brother take a dip in the pool at the same time? Why does the father shout and bully his son? They catch it right away. Of course, this is a reflection of the times in which Głowa na tranzystorach (“Head on Transistors”) or Dziewczyna i chłopak (“Girl and Boy”) were made, but still, Pippi Langstrumpf wasn't serving anyone breakfast.

Recently, I made an attempt to persuade my older son to read Małgorzata Musierowicz. When I was his age, Jeżycjada brought me a lot of fun. I experienced disappointment with the subsequent volumes of the series and, over time, in the earlier ones too, I saw the foreshadowing of a later tone that began to displease me. Nevertheless, until early adulthood, this series soothed and entertained me. I'm reading Kłamczucha (“The Liar”) with my 11-year-old. We laugh, we quote, but no great chemistry so far.

I recently came across a new edition of Niziurski's books in a bookshop and bought my son Stawiam na Tolka Banana ("I Bet on Tolek Banan"). It's got to work this time!

I suggest books to my children patiently, and I am not discouraged by failures, but they also discover new worlds for me. Thanks to my older son, I got to know Harry Potter, and I think J.K. Rowling should get some kind of honorary award for promoting reading among children. We have read the whole series together, and now the younger son is exploring the subsequent volumes with his dad. This is great literature that not only binds the reader but touches on life's most important themes.

Is it really as bad as people say when it comes to reading among young people?

I keep hearing that it is disastrous, but from my perspective - it is pretty good. My sons are bookworms. Their friends tend to read too. They talk about books and tell each other about them. The difference between us and them is that they have more learning and more suggestions for how to spend their time. And remote education ties them even more tightly to their screens. Here is a pandemic hint from me to parents of younger children. For my seven-year-old, I have introduced a rule that he can play as much as he reads during the day. It works like gold!

I assure you - there are quite a few children who not only play, but also read and listen to audiobooks, talk about what they have read, and live within those stories.

The publishing market also has its own ways of making the youngest readers fond of it. For children and young adults, books come out in series. They are accustomed to them from an early age, there are books about the adventures of Kicia the Kitten, Connie, or Max, then there is the Whodunit Detective Agency and the adventures of Pettson and Findus. And early teenagers reach for Brandon Mull's Fablehaven or Rafał Kosik's Felix, Net and Nika, which already has a dozen or so volumes. Children read one after another.

Constitution Square is probably a great place for all kinds of observations.

Constitution Square (a major square situated in the central district of Warsaw – translator’s note), is Poland in a nutshell. Most political and historical events were presented on it from the very beginning. After all, it was constructed in honour of Joseph Stalin. It also had a special function: it was where the demonstrations on 1 May and 22 July ended. It was a space created to manifest the only right views of the time. Now too, there are parades marching across it: sometimes rainbow ones, sometimes brownshirt ones. From my windows, I observe what hurts the Poles.

As Constitution Square is located in the very centre, it reflects the changes that are taking place in the city. When I moved here 11 years ago, the huge premises on the ground floor were occupied by banks and mobile telephone companies. They have all moved online. Now, slowly and laboriously, bars and restaurants are moving into Constitution Square, although it is still a place that is searching for its own identity.

Why did you choose this particular place and time as the background for the plot of Constitution Square and Dziewczyny z placu ("Girls from the Square")?

This place was waiting for someone to tell its story. If I did not do it, someone else would. At the very beginning, in the 1950s and 1960s, a privileged group lived here. Interesting people, building Polish communism, employees of ministries or directors of socialist enterprises. Their children are the notorious 'banana youth'. Indeed, they had access to bananas, shops behind yellow curtains (dedicated commercial outlets to serve the privileged representatives of the new government apparatus – translator’s note), and more money than the average Pole.

There was a lot going on in Constitution Square - the splintering of the 1956 revolt, and 1968 was more visible here than in other parts of Poland. It left a lot of empty flats in and around the square. Nearby, on Mokotowska Street, was the so-called "Region", the headquarters of Solidarity, where the people of Warsaw gathered on 13 December 1981, seeking information and encouragement. From there, they were chased away by ZOMO units using water cannons. Not far away is also the Avenue of Roses with a writers' tenement house and the most beautiful street in Warsaw - the Avenue of Friends with modernist buildings inhabited by party dignitaries and people who had and still have a great influence on the way Poland looks today.

One of the flats was occupied by "Bloody Luna", i.e. Julia Brystigier, a functionary of the communist security apparatus accused of torturing interrogated men at the Ministry of Public Security, which was also located nearby. Her bloody legend is enduring and strong, but it reportedly cannot withstand a clash with the facts. Józef Cyrankiewicz, Jakub Berman, Jerzy Waldorff or - since birth - Adam Michnik, a friend of my protagonists from Constitution Square and Girls from the Square, also lived in the Avenue of Friends.

Near the square, there is also Koszyki Hall; once a marketplace, today - a piece of London or Berlin on Koszykowa Street - a realisation of the desires of well-to-do Varsovians. An eminently ’warszawka’ (derogatory term for stereotypical inhabitants of Warsaw as a group - translator’s note) place to eat and drink.

Finally, there was Niespodzianka café on the ground floor of my block of flats, where Jan Lityński, Jacek Kuroń, Tadeusz Mazowiecki and tens of thousands of volunteers prepared Solidarity to partially win the June elections in 1989. They were even visited by Stevie Wonder, who came to Warsaw for one of the first big concerts at the Stadion Dziesięciolecia. He wanted to express his support for Solidarity, he sang I just called to say I love you, and Kuroń swayed beside him and pretended that he was also singing into an imaginary microphone. In the new Poland, on the other hand, wild capitalism flourished on the square, plastic booths with Chinese food, it was ugly and folksy. After all, this was our "American dream".

In 2011, on the other hand, the organisers of the Independence March fought a regular war in front of my window. They tore up cobblestones, threw things at policemen, and shouted "use a sickle, use a hammer, smash the red rabble". At the same time, shielded by a cordon of police, members of the Colourful Independent sang All you need is love. A couple of years later, the Equality Parade passed through the square to the tune of Girls Just Wanna Have Fun for almost two hours. This was after the rainbow installation had been erected a hundred metres away in Plac Zbawiciela (Saviour Square), which was regularly set on fire as part of an exchange of views.

How could I pass by all these stories indifferently?

Social realism in everyday practice... is it panache, impressive urban planning, friendliness?

All of them. It is a very comfortable place to live. Spacious staircases, landings, convenience. No developer today would leave such spaces in a staircase just so neighbours could stop and chat. It is immediately apparent that the blocks of flats were built on the foundations of an entirely different idea than making money on every square metre. Big windows, sizable flats - although not all of them. Different people with different needs were to live in the MDM Housing Estate.

Today, this place is already historical, the large bas-reliefs of a miner, a steelworker, or a teacher are no longer politically or ideologically charged. The creators did not foresee that there would be so many cars, trams, and such a crowd in the city. But still, this place has many positive sides. After the war, the bright square surrounded by ruins made a great impression on virtually all of Warsaw's tired people, who nested in several families in a single flat. Everyone wanted to live here. Today, some flee to quieter neighbourhoods, but there are those for whom this large, pompous, slightly bizarre and scaled square is a dream place to live.

What is it like to move from the position of a journalist to a writer?

It is still happening, the process is ongoing. Of course, years of writing reportage and interviews allow me to control the language much more skilfully than if I had not had such experience. It is also easier for me to do solid documentation. However, writing a novel requires overcoming far more uncertainties and fears than writing reportage. A writer is left alone with his or her thoughts, sensibilities, experiences; a journalist somehow relies on the ’flesh’, i.e. on facts or other people's statements. Some of it is similar writing, and some very different.

Tyrmand wrote a lot about Warsaw. Do you value his Zły (“The Man With White Eyes”)?

Tyrmand is very much associated with Warsaw, primarily because of The Man With White Eyes. I am not a fan of this novel; I feel that it is a product that has been tailored exactly for its time by a very skilled tailor. Times have passed and the charm has gone. And this Warsaw of his from The Man With White Eyes doesn't really thrill me either. Maybe that is why all attempts to transfer this novel to the screen end in a fiasco. Directors try to tackle this text, but nothing ever comes of it. I value Dziennik 1954 (“Diary 1954”) much more because it is partly created, it is not strictly a diary. It presents Warsaw and Tyrmand as he was. Or rather, what he wanted to be perceived as.

Who else wrote interestingly and nicely about Warsaw?

Warsaw has had, and still has, its many eulogists - from Prus, through Hłasko, Sylwia Chutnik, Twardoch, or Marek Nowakowski. Apart from Sylwia, these are all male stories and Warsaw is still told from male perspectives. I miss women's Warsaw trails, women's points of view, women's issues, and women's paths. This is one of the reasons why I wrote my Warsaw novels.

Do you happen to follow any Warsaw trails beyond the literary ones?

To be honest, Warsaw rings most in my ears thanks to the music. When I used to come from Krakow to attend classes at the Laboratory of Reportage at Warsaw University, “Miasto mania” was playing in my head. Maria Peszek has created an excellent, comprehensive portrait of Warsaw, still relevant today.

My Warsaw is present in Pablopavo and Fisz, but also in completely different stylistics, i.e. in the mischievous songs from Praga performed by Łukasz Garlicki, or on the album "Nowa Warszawa" by Stanisława Celińska. When I hear her sing “Warszawo ma”, I cry every time. There are also films - all those communist stories we have in our hearts, in which Marszałkowska, Aleje Jerozolimskie, and Woronicza streets flash by. This is the Warsaw I love. This is the Warsaw I know.

Interviewer: Andrzej Mirek

Translated by Justyna Lowe