News

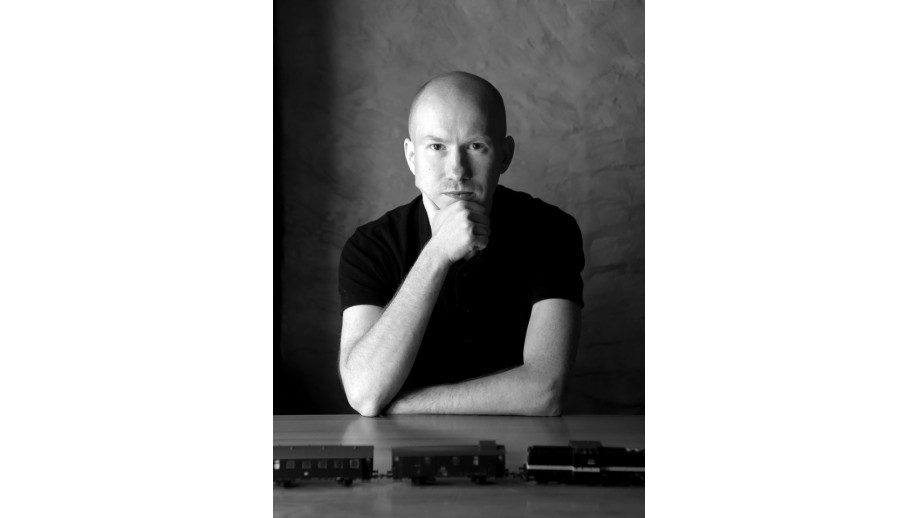

Bedside table #28. Piotr Milewski: Apparently, I have been saying repeatedly since primary school that I’m going to write

Piotr Milewski, a writer and traveller, talks about the masters of travel literature, what he is looking for in travel literature and literature in general, about the literary reasons for his trip to Japan, arranging the world by poetry, as well as about Mariusz Wilk's books and his constant returns to Nicolas Bouvier.

What are you currently reading?

I am reading a book by a Japanese writer, Jun'ichirō Tanizaki, In Praise of Shadows. An essay on Japanese aesthetics.

It was published by the Karakter publishing house. It’s a classic, isn’t it?

It's a classic indeed. It's very good that Karakter publishing house found this book and published it. It had been published earlier in Poland actually, yet it was absent from the market and, apart from good libraries, practically unavailable. It's about how the Japanese feel, think, and what they are like, or rather, what they were like. To me, it's interesting because, on the one hand, I can compare the present with the past, see what has changed, and, on the other hand, what hasn't changed, some deep core of their personality, which probably is still there somewhere.

Have you been delighted by something recently?

Staying on the Japanese theme: I've recently started reading Donald Richie's The Inland Sea. It's a book about a journey, but essentially, it's about a country, people, and a world that has passed. It’s about nostalgia, which, in my opinion, is something that we have in common with the Japanese. I started reading it, and I can't wait to get back to it.

Do you have favourite authors of travel books?

The master in this field is for me the French-speaking Swiss from Geneva, Nicolas Bouvier, published in Poland by Noir Sur Blanc publishing house.

Are you talking about The Japanese Chronicles?

Yes, indeed. He also wrote L'Usage du monde (“The Way of the World”), one of the classic travel books in which travelling is just a pretext. We will of course find a description of the journey in it, but in fact, what is more important is what the author feels, how he perceives and interprets the world. Although the journey he describes took place in the 1950s, you can read it at any time and still discover something new - it's a book I always have at hand.

So, in this kind of literature, you're rather attracted to what is somewhat close.

Descriptions in travel literature are something obvious, the reader is introduced to what is seen, the world. But what is more interesting is how this world is perceived, interpreted, and - recalling the title of Bouvier's book - how it is tamed. Only then does the journey take on a sense of meaning, apart from pure tourism. That's why Bouvier is the most important author for me. I got to know his books from The Way of the World, then, there was The Scorpion-Fish, a description of his six-month stay in Ceylon (as Sri Lanka was called at the time). It’s a description of extreme exhaustion, when Bouvier starts talking to the spirits of the dead, and all this is still travel literature.

You can't forget about these books, at least I can't - I have to return to them all the time. I have my favourite paragraphs to look at; I return to Bouvier during the weaker moments of my life. When I read it, I feel a kind of fraternal bond, even though, of course, I have never met Bouvier...

And you won't have a chance.

No, I won't. There is something that we have in common, and I know that if we met, we would have something to talk about and it would not be an idle conversation. Another important author to me is Bruce Chatwin, a British author who became famous for his book In Patagonia, which, as it turned out later, was quite heavily coloured, but this does not invalidate its literary values. What is also important to me is his Anatomy of Restlessness, a book about why we move, why we have to change our place, why we travel.

Is this the book that starts with an essay on Timbuktu?

This essay is in the first chapter. The book opens with the text I’ve always wanted to go to Patagonia with the subtitle How I Became a Writer. Patrick Leigh Fermor, published in Poland by Zeszyty Literackie publishing house, is also an important author for me. I love his little book A Time to Keep Silence about his sojourns in French Monasteries. He also wrote about the Peloponnese in his famous book Mani - Travels in the Southern Peloponnese. Reading this book, I immediately thought about Próba opisania krajobrazu greckiego (“Attempt at a Description of the Greek Landscape”) by Zbigniew Herbert and his descriptions of Greek experiences in Labirynt nad morzem (“The Labyrinth on the Sea”). Even though they are authors from completely different places, there is something that they have in common.

Talking about Herbert, do you read Polish authors of travel books?

I value Mariusz Wilk, his Wołoka (“Voloka”) and Wilczy notes (“The Journals of a White Sea Wolf”). These are books that have opened my eyes to the flexibility of the Polish language. In a way, they showed how closely our language is still connected with Slavic languages, and that it can be put to use and done with great artistry. At the same time, it is prose in which the moment and emotion is very important. Mariusz Wilk is very close to me.

And besides travel literature, what do you reach for?

I like other books, not non-fiction books. At some point, I was very keen on discovering Japanese literature, and a few books remain in my memory to this day. I return to them after some years and read them again, having the impression that I am reading them anew. They include, among others, The Woman in the Dunes, a very well-known novel by Kōbō Abe, or the book by Yukio Mishima, which was published in Poland under the title Złota pagoda (“The Temple of the Golden Pavillion”). I also return to Snow Country by Yasunari Kawabata, who was a close friend of Mishima and committed suicide two years after his death. Kawabata, as one of the two Japanese - next to Kenzaburo Oe - is a Nobel Prize winner. Snow Country is a very atmospheric book describing a world that does not exist anymore and never will, in which I would like to live, experience, and see one day.

I must admit that when reading Mishima, I had the impression of alienness, experiencing something I do not understand, but I appreciated the beauty of the language.

It was amazing to me that when I started reading Japanese books, I felt almost at home.

Did you start reading them before you went to Japan?

Yes, I went after reading the first few books and that was one of the motivations. I did not feel out of place during the reading, and it somehow encouraged me to try.

Besides, poetry is important to me, because - at least in terms of language - it arranges the world. It is able to put certain emotions, conditions, and experiences in words, which, as prose, would require a few paragraphs. Poetry can sometimes express this in a single line, in a single stanza. Różewicz, Szymborska, Bertold Brecht are very important to me - there was a moment in my life when I read his poems avidly, even in the original. And also, Shuntarō Tanikawa, whom I translated, and who also describes the world in such a way that it speaks to me.

Was there a book that made you think about becoming a writer? Or did it come from somewhere else?

Apparently - because I don't remember it – I have been saying even as a primary school pupil that I'm going to write, I’ve been saying it repeatedly. It happened much later. I still remember the book Zew przestworzy - opowieść o Żwirce i Wigurze („The Call of the Sky – a Story about Żwirko and Wigura”). I read it three times in my childhood I think, and it stuck right in my head. It was on my shelf, and I used to return to it often. Maybe it was this book that awakened the need for movement, which later materialised.

Then, of course, there was the story O psie, który jeździł koleją (“Lampo, the Travelling Dog”), and I still remember it today. A universal story that appears in many countries - sometimes the animals change, but the idea is similar. If I were to point to a specific book, it would be the one about Żwirko and Wigura though. I was delighted by it, and something started to sprout in me.

What are you looking for in literature?

I think I'm looking for a description of emotions, something that allows us to describe in words some emotional state, experience, not in a literal sense, something that grabs the heart or throat and makes us unable to break away from it. This is probably the most important thing.

Do you ever reach for prose?

Among Polish authors, I really like Hubert Klimko-Dobrzaniecki, who wrote about Iceland, he spent ten years there, so he knows it well and can judge it soberly. He knows its advantages as well as those aspects that are not very pleasant and that we, as tourists, usually do not see. I recommend his diptych Dom Róży. Krýsuvík (“Rose’s House. Krýsuvík”). Rzeczy pierwsze (“First Things”) is also interesting, just like his other books, which are half fictional, half biographical - at some point, we do not know where the facts end and where the creation begins. His new novel, Złodzieje bzu (“Lilac Thieves”), is about to be published, and it will surely be another surprise. I also value Maja Wolny; she has published the book Powrót z Północy (“Return from the North”), which begins with the protagonist's journey on the Trans-Siberian railway, which, by the way, is very close to me, as I devoted my first book to it.

Interviewer: Krzysztof Cieślik

Translated by Justyna Lowe